Maybe it's just me, but I believe the fever is starting to break on AI. I don't mean that it's going away, but I mean that we are starting to settle on the new normal. Creating funny videos with Sora, using ChatGPT as a search engine, coding with Claude, and whatever is going on over there with Grok, won't be the sole purpose of AI. Many have already stated this, but AI will become a new utility. Similar to electricity, and water. It will be ingrained in everything we have. Following the analogy of electricity, on its own it's rather useless to us. However, twist a light bulb into a socket, charge your phone, run an air conditioning unit and suddenly electricity is core to our comfort.

AI is likely to take the same future path. While many of us are creating videos, forming relationships with chat, and using it as a novelty, the real power is in how decisions are going to be made, and how technological breakthroughs are discovered. So, while the words "AI bubble" are being thrown around, the reality is that AI will continue to evolve and isn't going anywhere. So, perhaps as Clem Delangue, the co-founder of Hugging Face, put it, the AI bubble is a mislabeling of what is likely an "LLM Bubble."

What does that mean for the future of the technology? How it will look? And for those of us in cybersecurity, how will it be better or worse for our future use cases?

Understanding the inefficiency

While there is currently a large concentration of attention and money going to general-purpose chatbots, Delangue's prediction is that there will be "a multiplicity of models that are more customized, specialized." And we're seeing that today with small language models (SLMs) and "digital factories" with "workers and consultants" that are tailored to specific tasks and only those tasks (more on that in a moment).

Since the launch of ChatGPT in late 2022, when AI and LLMs became part of the everyday language, we've generally applied frontier models (ones that are considered general-purpose and trained with large computational budgets) to almost every feasible use case. This monolith fallacy meant that we were (and still are) throwing everything to these LLMs. Need a recipe for chicken parmigiana, a rewrite of a resume, a full research paper on quantum mechanics, production level code? It all went to the same trained model to respond. It's like hiring a well-paid cybersecurity architect to answer emails (I've been there; wouldn't recommend it.). Just like that architect, it needs to be asked whether your organization is overpaying for overqualified technology used for simple jobs.

To put a finer point on this, GPT-4 can parse a JSON file and extract specific fields. But using 100+ billion parameters to accomplish what a 50-line Python script (or better yet, a 7-million-parameter specialized model) could do is a computational waste.

In the context of cybersecurity, the waste becomes even more obvious. Consider a vulnerability scanning agent that uses a frontier LLM to analyze every log entry, classify every alert, and respond to every probe. You're paying premium compute costs for the model to:

-

Parse structured log formats (something regex excels at)

-

Match known vulnerability signatures (perfect for a specialized classifier)

-

Respond to obvious attack patterns with canned responses (literally rule-based logic)

-

Answer questions it's been specifically instructed to refuse

As Trend Micro puts it: "How much money are you burning having your frontier model answering with 'I am sorry but I cannot help you with that' to respond to would-be attackers probing your app?".

Parameters and smaller models

This is where a jack-of-all-trades versus a tailored model makes a huge difference. Frontier models tend to have large amounts of parameters (think of parameters as the knobs and dials used to help the model form a response). These large parameter models (in 10s or 100s of billions) can be prepared to answer everything and anything its thrown—largely because it's been trained and tuned on a vast amount of data. This makes them excellent at answering a question like "Write me a function that calculates the square of a number in Python, C#, and Java." However, this is overkill (perhaps even counter-productive) for a workflow that might only expect very specific inputs to produce a structured output.

Take the previous example of a model trained for alert triage and classification. An organization's historical SIEM alerts can classify incoming security alerts (true positive/false positive, severity, threat category) in 12 milliseconds with 94% accuracy, processing 30,000 alerts per day for $150/month. Compare that to using GPT-4 which takes 2-3 seconds per alert and costs $7,200/month while achieving only 87% accuracy because it lacks your environment-specific context. Your mileage may vary, but there is no doubt that there is more waste in using a LLM for this purpose.

We are now at a place where architectural finesse and innovation can utilize smaller models to perform specific workflows while keeping costs practical.

Enter the digital factory architecture

NVIDIA has put forth an architectural vision using a factory metaphor. SLMs are the specialized workers handling 90% of routine tasks. LLMs are the expensive consultants you call when workers get stuck or when you need strategic planning. A router analyzes each request and determines whether it needs the "$100/hour genius or the $0.01/hour specialist." This shifts the general purchasing of AI power from buying a complete LLM to purchasing workflows powered by SLMs.

Here is an example of this concept for a threat hunting and behavioral anomaly detection use case in a security organization.

LLM Consultant (70B+ parameters, $0.20/task):

-

Creative Hypothesis Generation: "Given recent geopolitical tensions, assume state-sponsored actors targeting our supply chain. What TTPs should we hunt for? Generate 10 hypotheses with corresponding detection queries."

-

Behavioral Analysis: "CFO's account shows normal email activity, but 47 emails auto-forwarded to external address over three weeks. No malware detected. Is this: (1) Legitimate business rule, (2) BEC compromise, (3) Insider threat? Recommend investigation approach."

-

Campaign Correlation: "We've seen 12 'low-risk' anomalies across different systems over 30 days—none individually alarming. Could these be reconnaissance for a coordinated attack? What's the connecting thread?"

-

Zero-Day Hunting: "No signatures exist yet. Based on this vendor advisory and our environment, where would an attacker target? Generate proactive hunts before exploitation begins."

-

Hunt Retrospective: "We hunted for X but found nothing. Were our assumptions wrong? Should we expand scope? Or is this genuinely clear?"

SLM Workers (1B-7B parameters, $0.001-0.003/task):

-

Baseline Profiler (Worker #1): Continuously learns "normal" for each user/system (login times, locations, process patterns, network destinations)

-

Anomaly Detector (Worker #2): Flags deviations from baseline (e.g., "user logged in from new country," "process spawned unusual child")

-

Entity Resolver (Worker #3): Links entities (user → multiple IPs → multiple hosts) into coherent profiles

-

Pattern Matcher (Worker #4): Checks against 500+ known attack patterns (e.g., "certutil used for file download," "unusual scheduled task creation")

-

Risk Scorer (Worker #5): Assigns numeric risk score based on anomaly severity, asset criticality, user privilege level

-

Hunt Query Generator (Worker #6): Translates high-level hunt hypotheses into SIEM/EDR queries (Splunk SPL, KQL, Elastic DSL)

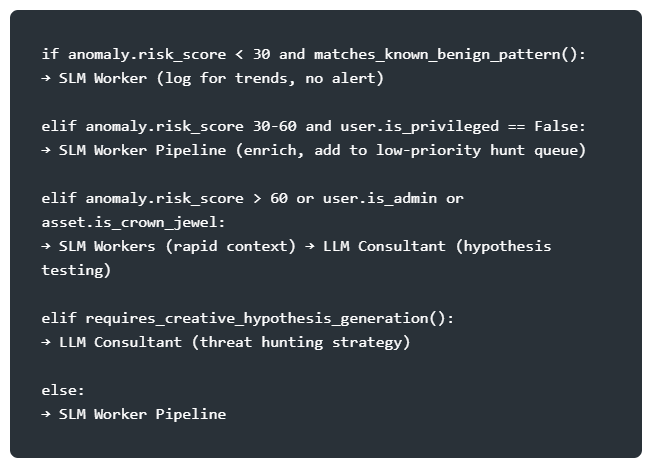

Router logic:

This is just an example, and the factory can be tailored to meet the organization's needs, but the important takeaway is that utilizing smaller, purpose-built models are more cost-effective for certain tasks. But there's another benefit.

Security through compartmentalization

Those of us in cybersecurity know the principles of least privilege and separation of duties. Building architecture around SLMs can provide both. When you employ a handful of SLMs for specific tasks, you limit the scope of what those models can do while ensuring that each SLM only works on their part of the system.

However, the concern of model sprawl can lead to anxiety over an expanding attack surface. Do more models mean more possible attack points? Possibly. But we must consider that monolithic models can be a single point of failure. If your single LLM that is used to power your entire system is compromised, you have a single point of failure. Breaking up that model into a heterogeneous system can provide compartmentalization and enable a stronger defense in depth. In this scenario, a single compromised SLM can be shut down, impacting a single workflow, compared to fire-fighting a compromise of your primary LLM.

The path forward

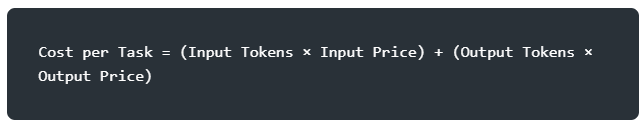

Here are a few takeaways to consider. Begin by auditing your current AI spend and how it's being used. Which tasks actually require a frontier model versus a more tailored SLM? Look for repeated, bounded tasks that can be good candidates for SLM work. In terms of costs, most models charge by token, so a simple formula like below might get you a basic idea of costs:

Additionally, look at security tasks that are ripe for SLM implementation. Workflows like log analysis, anomaly detection, threat intelligence summary, policy Q&A chat, or code review for specific vulnerability classes are all examples of quick wins with an SLM in a security program.

Lastly, look to implement router-based model architecture that is triggered based on request complexity. Simple queries go to the SLMs, where more complex queries requiring reasoning go to the LLMs. However, ensure that you compartmentalize the models by trust levels and data access requirements to reduce the blast radius and protect sensitive data.

We are likely going to continue to see a rebalancing of how AI is used in organizations as the costs versus value equation requires us to reevaluate how AI is used in our systems. Some projects are likely to fail without a clearly defined ROI. But we're in a position now to stop trying to build the "all knowing AI" and focus on more targeted uses of the technology.

This article appeared originally on LinkedIn here.